|

Image by Jacques GAIMARD from Pixabay

I admit when I was a high school student history bored me as it probably bores many high school and college students today. But, I don't think my boredom was inevitable nor is the boredom of today's students. Boredom is not a central feature of history though it is often central to the teaching of history. This is due in large part to textbooks that lack interest and teachers who lack passion and a skill for storytelling. When you get right down to it, history is first and foremost story. But, this is rarely stressed in the classroom and almost never stressed in the textbooks. Fortunately, there are resources to counter this problem. Let's consider a few which emphasize not only the story aspect of history but also the fact that everything has a history.

0 Comments

There's a large and growing body of research on best practices of teaching. Most of it seems premised on the idea that we know exactly how students learn and therefore we know exactly how to teach them. It is largely based on the behavioral model of psychology. Push a button, get a response. I think there's an inherent dishonesty at work in this research on teaching and learning. Dishonest because it denies an inherent complexity and subjectivity which lies at the heart of teaching. Take a look at this picture: Which orange circle is bigger? The one of the right?

Now, look at this next picture:

Image by Marc Pascual from Pixabay

There is a continuing debate among academics concerning what we should be teaching our students. If we were to listen to the students themselves, we would only teach them what they are interested in learning. But that begs a very important question. How can you be interested in something you haven't yet learned? No, the proper role for the educator is to teach what, in their judgment, needs to be taught. How can they make such judgments? Well, the answer is never easy but I think it is fair to defer to experience in these situations. And no, I'm not talking about the individual experience of one or two professors or instructors. I'm talking about the collective experience of our cultural patrimony. Which is only one of the reasons I am an advocate of cultural literacy.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

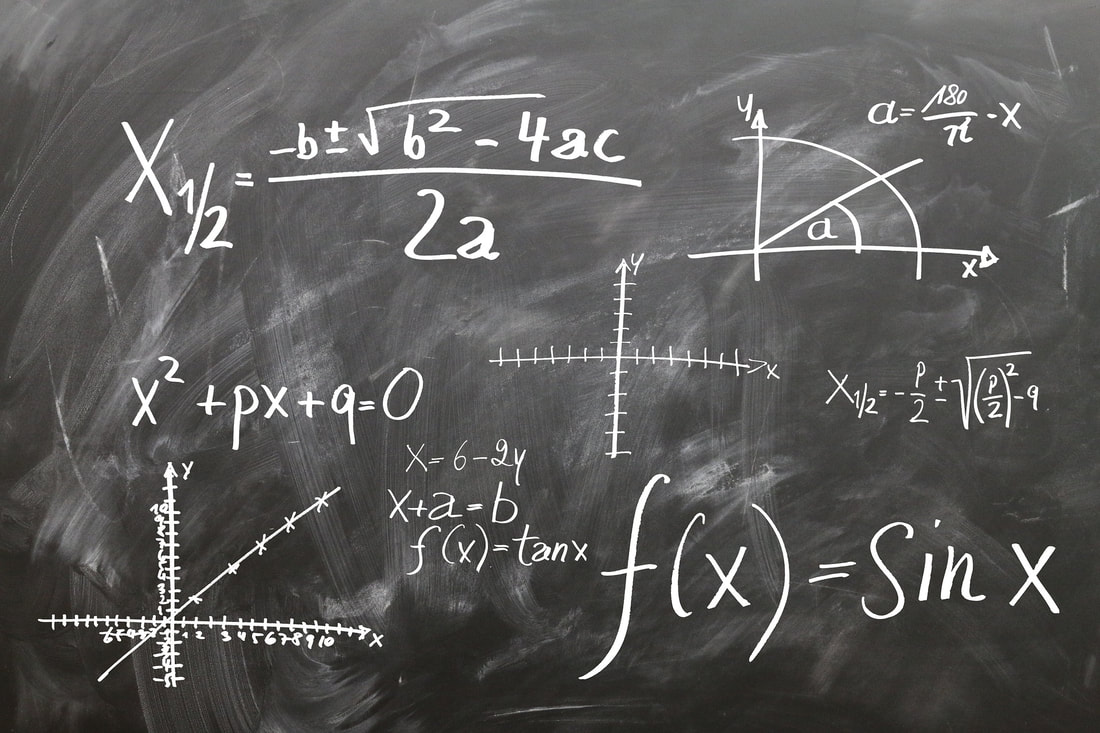

You hate math. I get it. But, you probably are basing your intense dislike of math on an extremely limited sense of what math entails. You’ve been taught that math is numbers and calculating. Memorizing difficult formulas and solving word problems about trains going in different directions for no particular reason except to torture you. But, math is much, much more. Math is about beauty. And symmetry. The glorious patterns of nature and movement. Math can enrich your understanding of dance, music, art, and design. But, to appreciate this feature of mathematics you will need to go far beyond the textbook. Not “far beyond” in the sense of advanced mathematics but “far beyond” in the sense of venturing away from the mechanics of mathematics to the underlying point. There are some excellent resources to help deepen your understanding and appreciation of mathematics. Let’s look at a few.

The National Geographic-Roper survey of geographic literacy is now famous for its findings regarding American school-age kids. Many do not know the basics of geography. A few of the more disturbing findings are as follows:

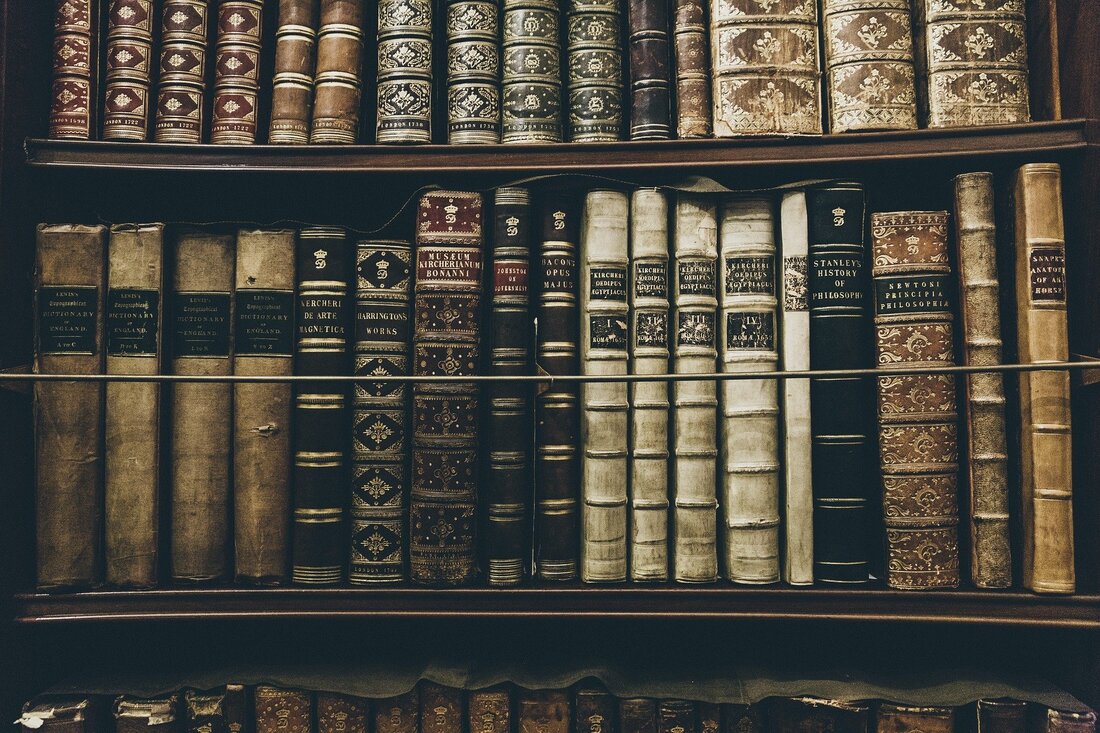

At some point this year (2022), I will read my 2,000th book. I thought I'd revisit a post I made years ago regarding my 1,000 book milestone. On September 10, 2010, I read my 1,000th book. I started counting books I completed in 1987 so it took a little over 20 years to reach my 1,000th book. Upon reaching the milestone of reading 1000 books, it seems appropriate to reflect on what I have learned as a result of all that reading. The temptation is to enumerate a list of facts or insights gained from individual books. Doing this might be a worthwhile project but would be a book unto itself and might not yield any insights to other readers. Instead, I want to reflect on a few general points.

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

A popular topic of education reform articles lately is the subject of student engagement. A common diagnosis for the lack of student engagement is that students are not finding the information presented in class relevant to them. The proposed solution is often that professors must show students how the subject they’re studying really is relevant. I disagree! If students are not finding the subjects they study relevant, then they are not looking for relevance. Why is it that professors must point out relevance? What responsibility do students have for making their education meaningful?

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

When I teach ethics one of the questions we discuss is: Does everyone have different morals? Nearly every student answers yes. I find this an odd and inaccurate answer. But, even when presented with evidence for the sameness of our moral principles they remain unconvinced and continue to focus on the differences to the exclusion of any focus on our common moral foundation. Inasmuch as this has some pretty important implications for our moral discourse I'd like to posit some possible explanations for this focus on differences. With Valentine's day a day away my philosophical thoughts turn to love. There's more to the concept than meets the eye. A good book on this topic which outlines the various distinctions philosophers have made regarding the concept is Christopher Phillips Socrates in Love. In the book, Phillips outlines the five Ancient Greek concepts of love as follows: |

KEVIN J. BROWNEPhilosopher / Educator These blog posts contain links to products on Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed